Applied Science

Protecting Highways From Sinkholes

Sinkholes, both naturally occurring and human-caused, are a recurring problem around the world. It is especially problematic in southeastern New Mexico, west Texas, and other regions where much of the underlying bedrock is gypsum—a highly soluble rock. In 2008, an enormous sinkhole, over 100 m in diameter, formed overnight not far north of Carlsbad, New Mexico.

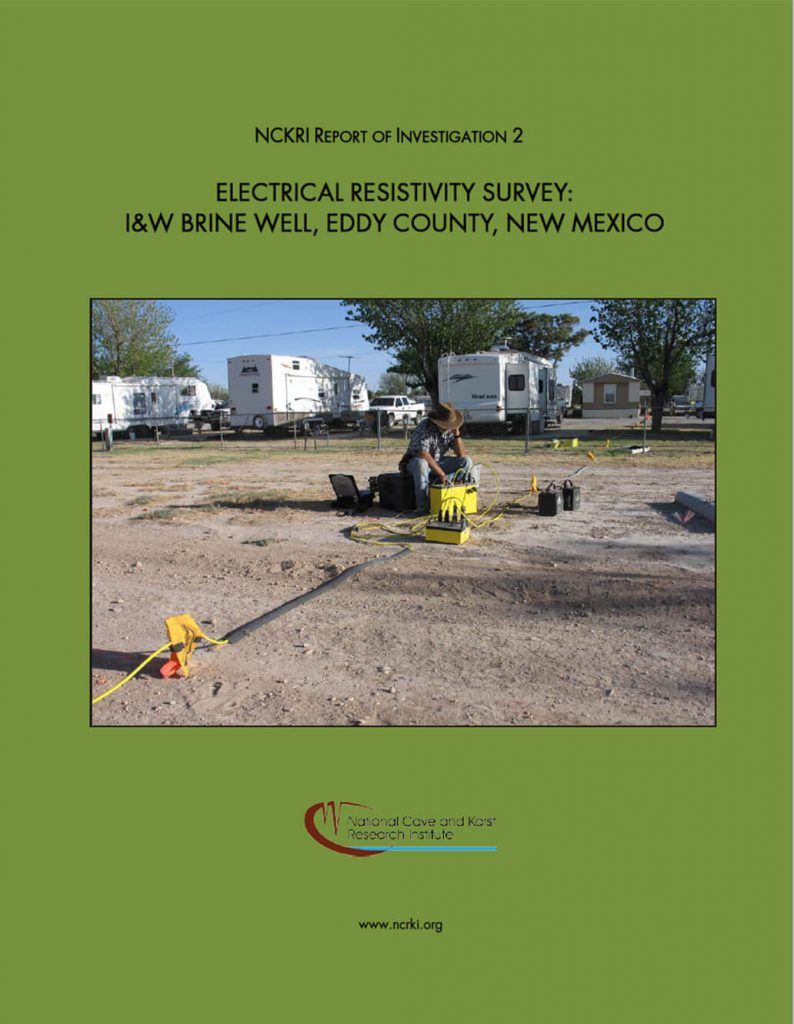

Human activity associated with a brine well operation caused the sinkhole. It prompted several investigations of karst geohazards that might affect the region’s network of highways. Many of these studies use near-surface geophysical tools, including electrical resistivity.

Electrical resistivity is a handy tool for identifying sinkhole hazards. Collecting and processing data can be done onsite, in a single day, using a ruggedized laptop computer and specialized software.

In 2018, the New Mexico Department of Transportation funded a NCKRI study of sinkhole hazards along Highway 285 from the town of Loving south to the state line. This section of highway has been called “the deadliest road in the United States” because of its narrow shoulders and extremely high oil field traffic. The potential for sinkholes to open suddenly on the highway increases the danger.

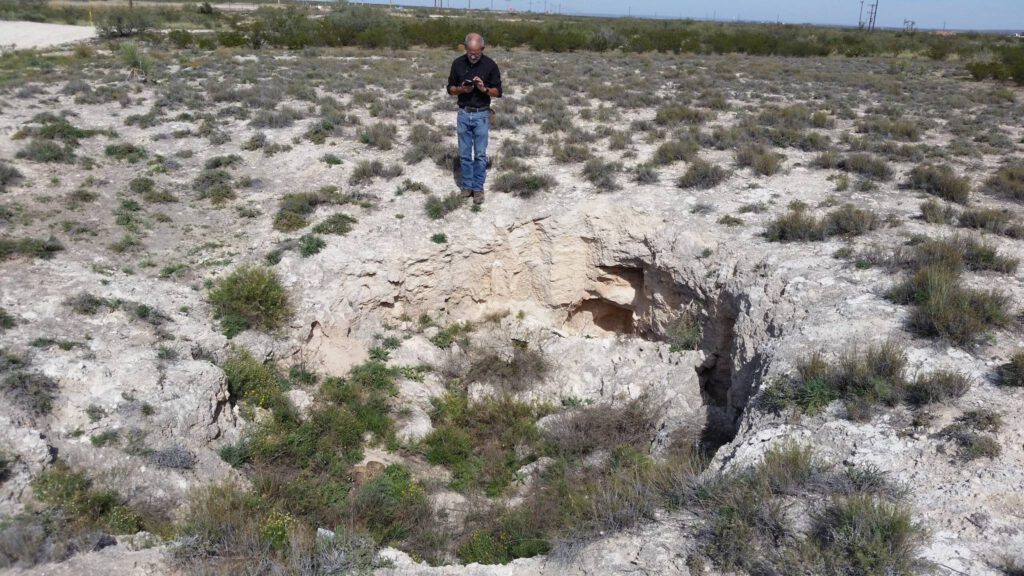

NCKRI scientists, assisted by New Mexico Bureau of Geology personnel, mapped the geology and examined karst features along the 35-km stretch of highway. From this survey, the team identified six areas with a high sinkhole hazard potential. Using electrical resistivity, those areas were intensively studied so the highway could be redesigned to minimize the risk of sinkhole damage. All these sites are located where gypsum bedrock of the Rustler Formation occurs at or just below the land surface.

San Solomon Springs Initial Investigation

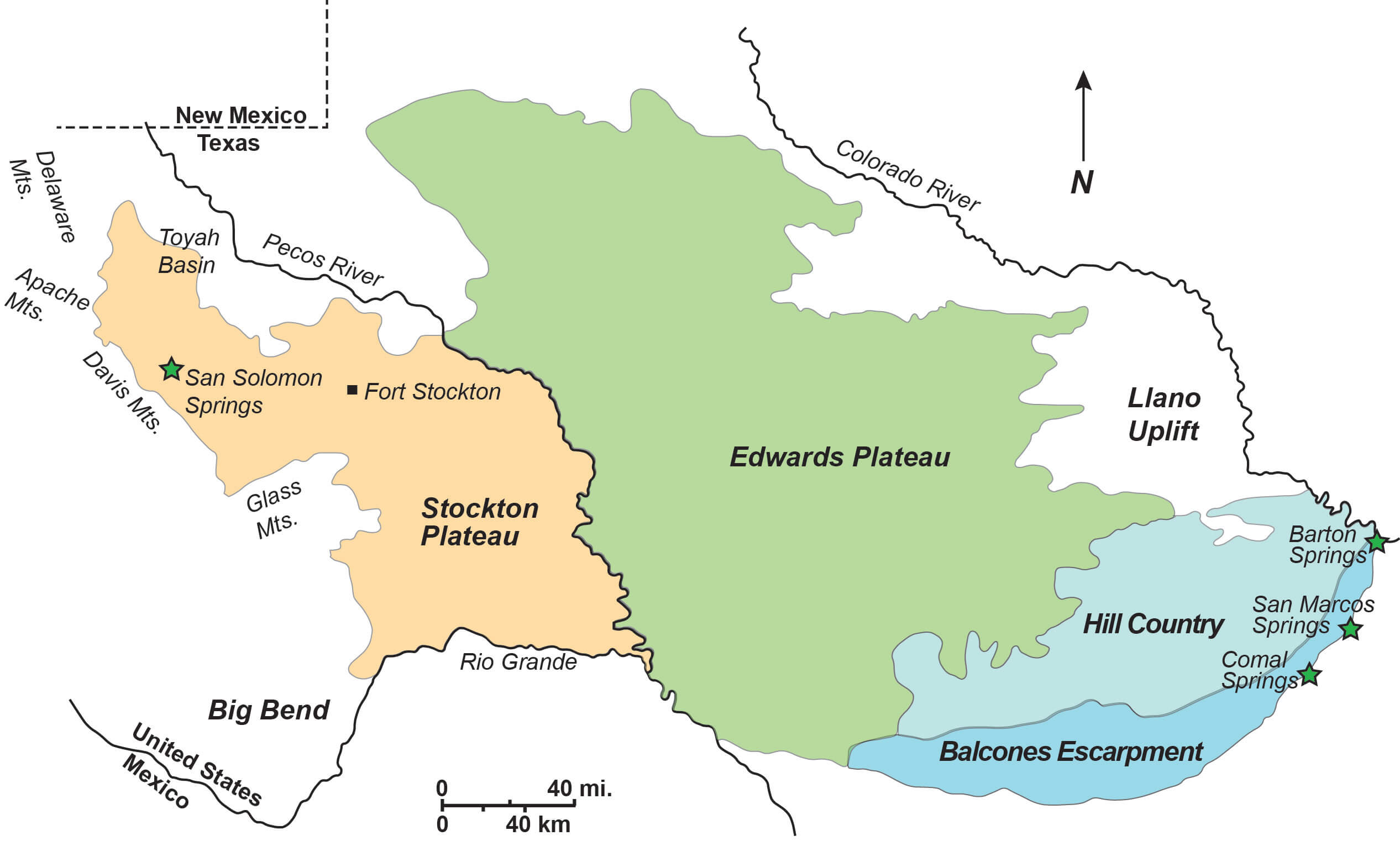

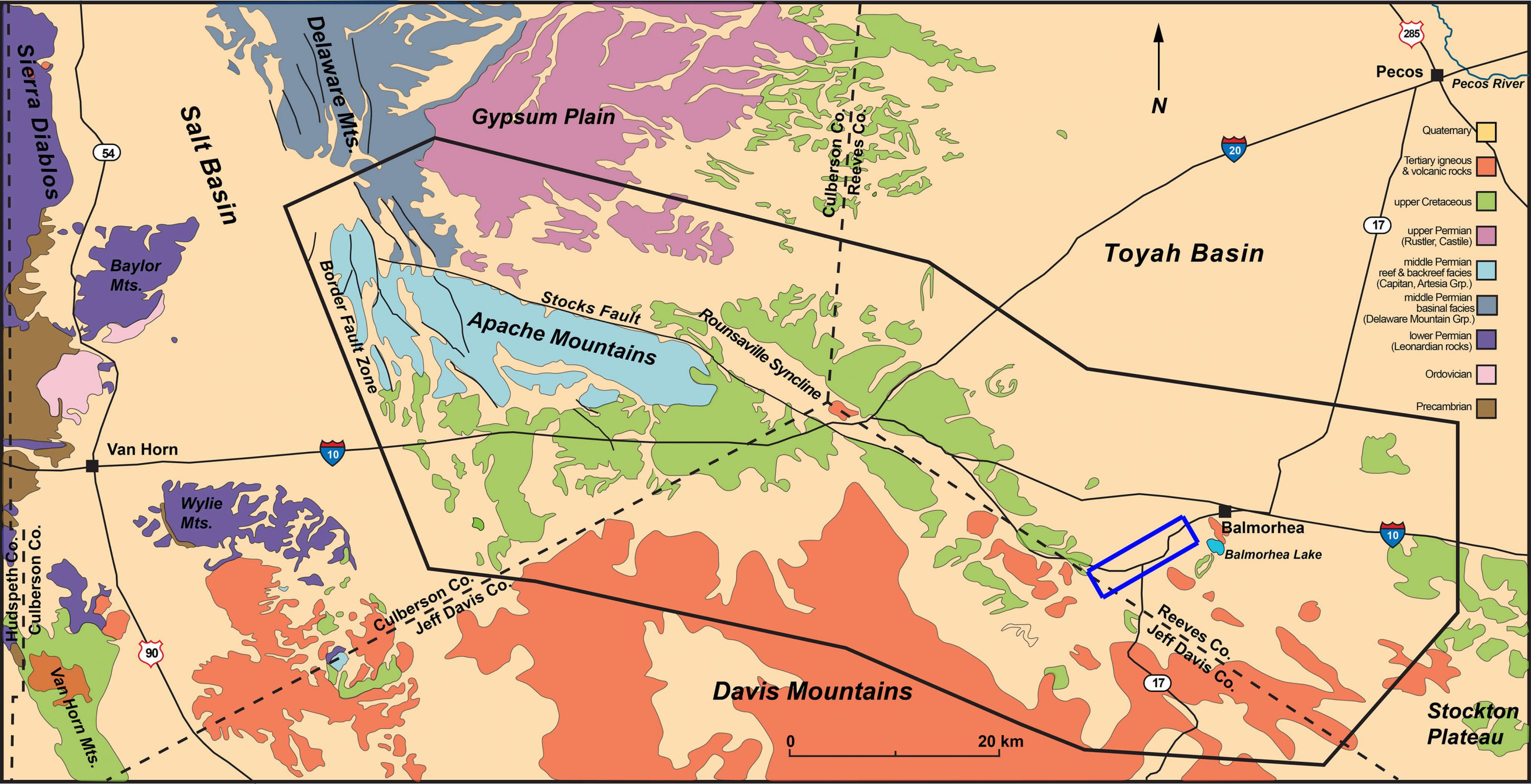

In 2017, NCKRI staff reviewed the literature for previous work on the hydrology of the San Solomon Springs Group. These karst springs discharge groundwater from Cretaceous limestones found along the northeast flank of the Davis Mountains, in far west Texas. The springs and their aquifer provide the water supply for much of the agricultural activity in the area. They also provide habitat for several federally listed endangered species, including the Comanche Springs pupfish and Pecos gambusia. The main San Solomon Spring is the centerpiece of Balmorhea State Park.

The Apache Corporation funded this research to avoid compromising the water resources of the San Solomon Springs and their karst aquifer. The company is in the early stages of developing a significant oil and gas discovery in the area.

The San Solomon Springs are located at the far western edge of the Edwards Plateau and the greater Edwards-Trinity Aquifer System, one of the largest karst regions in the United States. The San Solomon Springs area also lies within the boundaries of several regional studies of the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer conducted over the past quarter-century by the US Geological Survey, Texas Water Development Board, and The University of Texas.

However, our review indicates that the San Solomon Springs are part of a different aquifer system that has little to do with the Edwards-Trinity Aquifer. Based on water chemistry data, previous workers at The University of Texas-Austin concluded that discharge from the San Solomon Springs probably originates far to the west, from groundwater recharge in the Salt Basin in central Culberson County.

This water then flows through Permian limestones of the Capitan Reef in the Apache Mountains, and from there into Cretaceous rocks put in contact with the Capitan Reef by faulting near the east end of the Apaches. The hydrology of the area is thus fairly well-understood on a regional scale. However, a detailed understanding of the local and sub-regional groundwater flow system is needed.

Based on this review, NCKRI developed a plan for the systematic investigation of the San Solomon Springs system. (see NCKRI Report of Investigation 8) This study would include a program of water level measurements and groundwater sampling, in an area extending from southern Reeves County east of Balmorhea to the west flank of the Apache Mountains. This information would better characterize groundwater flow paths. Following the water level survey, NCKRI staff would collect water samples from selected wells. They would then test the samples for general chemistry and organic compounds that occur in crude oil. The Institute also recommended a series of dye traces to delineate the boundaries of the springs’ groundwater drainage basin, which would build on an existing dye trace conducted by NCKRI in 2013.

NCKRI has begun some of those proposed studies. Visit NCKRI’s Basic Research for news on that ongoing project.

Preventing a Catastrophe: The Carlsbad Brine Well Cavity

NCKRI’s mandates include supporting, facilitating, and promoting research. This report is on a crucial project we’ve worked on over several years to prevent a catastrophe from occurring in our hometown of Carlsbad.

In 2008–2009, three brine well cavities collapsed in southeast New Mexico and West Texas, creating sinkholes measuring up to about 100 m in diameter and 40 m deep. The cavities were formed by injecting freshwater into deep salt beds, thus dissolving the salt and pumping out the resulting brine for oil field drilling.

The I&W brine well cavity was identified at that time in Carlsbad near the intersection of two highways, an irrigation canal, the railroad, and several businesses. It was determined as unstable, and its operations were closed by the state.

These cavities are not karstic in the usual sense of a natural process. They are anthropogenic, human-created, karst cavities. Karst primarily involves the dissolution of rock, and these cavities formed by people injecting water to dissolve rock salt. The knowledge that NCKRI brings to this situation from natural karst features is valuable to solving this problem. There is no doubt that the knowledge NCKRI will gain from these anthropogenic features will prove useful to better understanding natural karst cavities and collapse events.

Since the initial collapses, NCKRI has served as a technical advisor to the City of Carlsbad and the State of New Mexico on the cavity in Carlsbad. Among our many activities, we:

- Performed a geophysical survey of the cavity;

- Participated in emergency planning exercises with the city, county, and state emergency personnel in preparation for a collapse;

- Educated the public about the situation through many guest lectures and meetings;

- Assisted personnel with the New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources with a drone flyover and down to the bottom of the JWS Sinkhole, the first of the three collapses that occurred in 2008–2009;

- Led and co-led several field trips for governmental and other groups to the collapses that already occurred to examine the likely impacts of a collapse in Carlsbad; and

- Determined that a collapse of the cavity in Carlsbad would cost over $1 billion in damages and economic impacts!

The Loco Hills Sinkhole collapsed in November 2008. In this photo, it is about 60 m in diameter and 50 m deep. It grew to about 100 m in diameter. Photo courtesy: NCKRI Staff Lewis Land.

Jim’s Water Service (JWS) Sinkhole collapsed in July 2008 and within a month grew to about 100 m in diameter. For scale, notice the small group of people at its upper right side. Photo courtesy: NCKRI Staff George Veni.

In 2017, we supported legislation through testimony to the New Mexico Legislature to create a Brine Well Authority, a governmental body to fill the cavity so that it never collapses. But there was a problem with the Brine Well Authority. It had money to hire a firm to create a plan to fix the cavity, but no money for the actual repair.

NCKRI then co-chaired the State’s Technical Committee to write a request for proposals for the State of New Mexico to contract an engineering firm to fill the cavity. While this sounds easy, it is actually a complex and delicate operation. The proposals needed to include all specifications for a permanent solution while minimizing the risk of inducing a collapse during the repair.

With that complete, in 2018, NCKRI served as the technical expert at the State Legislature, supporting the efforts of Representative Cathrynn Brown and Senator Carroll Leavell in getting the State to fund the repair. With literally only minutes to spare, the funding was approved.

Currently, the filling of the cavity is underway. The target for completion is before the end of 2022. Afterward, there will be a 2-year monitoring period to assure no substantial subsidence occurs that needs further repair. During this period, NCKRI continues to co-chair the Technical Committee and serves as a resource for the project as needed.

To be clear, while NCKRI played an important role in these efforts, we were part of an extensive partnership of governmental and private organizations, private citizens, and political leaders who made the funding a reality. NCKRI believes strongly in partnerships and is honored to be part of this team.

Want to Learn More?

View the reports below to learn more about the I&W Cavity and nearby brine well collapses.